Growth Versus Austerity: A U.S. Dollar Perspective Axel Merk, Merk Funds June 20, 2012 Austerity versus Growth? Which economic model is sustainable? If it weren’t for those pesky bond vigilantes, it may be only politics. Let’s not get too excited that either path will work. Let’s look at the implications for investors with a focus on the U.S. dollar.

To have budgets sustainable is as simple as matching revenue and expenses. Almost. Politicians have figured out that running a deficit may still yield a stable debt-to-GDP ratio, assuming there is economic growth. When U.S. politicians brag their budget forecasts bring down the absolute level of the deficit, it’s the debt-to-GDP ratio at best that may improve, assuming their rosy projections of economic growth prove correct. In the Eurozone, governments have – theoretically – committed themselves to running no more than 3% deficits, suggesting that such deficits lead to sustainable debt-to-GDP ratios. Not quite. Our research shows that, in order to achieve a long-term debt-to-GDP ratio in the low 50% range, deficits of no more than half of GDP growth may be run. If GDP growth is 3% a year, the deficit ought to be no higher than 1.5%. If 3% deficits are allowed, but GDP growth is only half of that – a more realistic assumption for many countries in today’s environment, the debt-to-GDP ratio will stabilize at above 200%. For a visualization of where the debt-to-GDP ratio will peter out given different growth and deficit scenarios, consider this table:

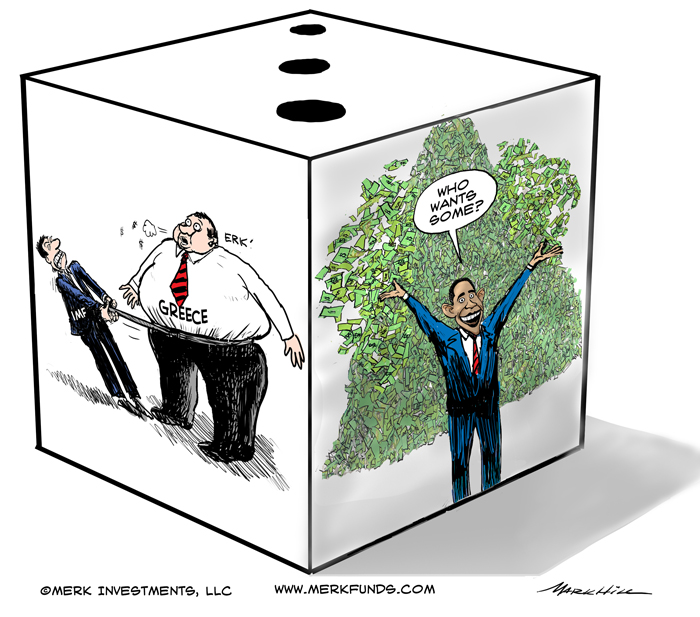

Why do we care about debt-to-GDP ratio? Allowing a high debt-to-GDP ratio is akin to playing with fire. Just look at the housing bust for an illustration as to what’s so dangerous about piling up too much debt: when interest rates are low, life feels great, the standard of living has gone up. But when interest rates move up, those with a higher debt load have to make disproportionate cuts to their standard of living to service their debt. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the U.S. paid an average of 2.2% of GDP in interest from 1972 until 2011. In its “Extended Alternative Fiscal Scenario” that assumes current policies, as opposed to current laws, remain in place, net interest payments will soar to 9.5% of GDP in 2037. In 2011, $454.4 billion in interest was paid in a $15 trillion economy; that is, 3% of GDP was spent in servicing interest payments. If the U.S. were to spend 9.5% of GDP to service its debt rather than 3%, it requires a cut of 6.5% of GDP in other services. It dwarfs the fiscal cliff (the reference to Bush era tax cuts running out coupled with spending cuts, absent of Congressional action) that might put a 3% to 5% dent on GDP. The pessimistic CBO outlook assumes what we judge to be an unrealistically low 2.7% average interest rate on debt payments. Should the market demand more compensation – generally referred to as bond vigilantes holding policy makers accountable – financing the deficits may no longer be feasible. Just ask Greece; or Spain. With 10 year Treasuries yielding 1.6% in the United States, some argue that higher deficits are warranted. As the discussion above shows, the logic behind the view is fundamentally flawed, if not reckless. In the U.S., we differentiate between discretionary and mandatory spending. Mandatory refers to contractual obligations, the entitlements, most notably regarding Social Security and Medicare. Put simply, it may not be realistic in the long run to finance thirty years of retirement with forty years of work. As interest payments take a bigger chunk of GDP, discretionary spending is squeezed out. Be that an infrastructure project at the federal level; teachers at the state level; or firefighters or animal shelters at the local level. In real life, there are some added complexities: we all fight for our benefits, take them for granted once granted and will fight vigorously to retain them. Also keep in mind that emergencies, such as natural disasters or wars, are typically not reflected in budget forecasts, as they might be considered “one off” items; even if that were correct, emergency spending adds to the deficit. As a debate rages whether austerity or growth is the solution to the plight of the developed world, keep in mind that there is a history spanning centuries, if not millennia, of governments spending too much money. In the old days, neighboring countries were “taxed” to fill domestic coffers: taxation, as in conquering other countries and taking treasures and slaves. Debt is a modern form of slavery, except that it is voluntary servitude. If history is any guide, don’t get your hopes up too high that these issues will be resolved. But investors may be able to navigate the waters, mitigate some of the risks or even profit from opportunities that arise in this environment. The growth camp suggests that, with enough growth, a high debt load can be carried. That may be the case if such growth is not financed through debt. In recent years, trillions have been spent to achieve billions in growth – not exactly a recipe for sustainable budgeting. The austerity camp suggests that, with enough austerity, books can be balanced. Except that, as services are cut, the economy is at risk of entering a downward spiral, increasing, rather than decreasing deficits. And while these two ideologies are being discussed, central banks struggle to either keep the banking system afloat (as in the Eurozone) or are helping to finance the government deficit (as in the U.S.). Indeed, the key difference between the U.S. and European model is that U.S. Treasuries appear to be backed by a) the taxing power of Congress and b) a lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve (Fed) with its printing press; whereas European sovereign debt is backed only by the taxing power of the national governments. The European Central Bank (ECB) has made it clear that its role is to support the banking system, not the sovereigns. In contrast, the Federal Reserve (Fed), while not admitting to outright financing of government deficits, has shown a willingness to do so in practice. As such, European sovereign debt is trading more like municipal bonds trade in the U.S., with weak “municipalities” (think Spain) paying a huge premium. To be fair, the growth camp wants more than deficit spending; and the austerity camp wants more than cost cutting. Indeed, in a recent analysis Saving the Euro, we argued policy makers should instead focus on competitiveness, common sense and communication. Ultimately, both camps believe their philosophies should attract more investment as confidence is increased. In practice, the proverbial can is kicked down the road. By the time the can reaches the end of the road, it may be very beaten up. Indeed, an increasing number of investors are spreading their investments across multiple “cans” – we refer to these “cans” as diversified baskets of currencies, including gold. What’s different between the U.S. and Europe is that the U.S. has a significant current account deficit. In our experience, countries with current account deficits tend to favor growth oriented strategies as they need to attract money from abroad to finance their deficit and, as such, to support the currency. While a bond market in shambles is a major drag on growth in the Eurozone, the Euro has been able to hold up reasonably well given the fact that the Eurozone’s current account is roughly in balance. A misbehaving bond market might have dire consequences for the U.S. dollar, even if one disregards the odds that the Federal Reserve may make U.S. Treasuries even less attractive by financing government spending (when a central bank buys a country’s own debt by printing money, such securities are intentionally over priced, potentially weakening the currency). Please make sure to sign up to our newsletter to be informed as we discuss global dynamics and their impact on currencies. Please also register for our upcoming Webinar on July 19. We manage the Merk Funds, including the Merk Hard Currency Fund. To learn more about the Funds, please visit www.merkfunds.com. Manager of the Merk Hard Currency Fund, Asian Currency Fund, Absolute Return Currency Fund, and Currency Enhanced U.S. Equity Fund, www.merkfunds.com Axel Merk, President & CIO of Merk Investments, LLC, is an expert on hard money, macro trends and international investing. He is considered an authority on currencies. The Merk Hard Currency Fund (MERKX) seeks to profit from a rise in hard currencies versus the U.S. dollar. Hard currencies are currencies backed by sound monetary policy; sound monetary policy focuses on price stability. The Merk Asian Currency Fund (MEAFX) seeks to profit from a rise in Asian currencies versus the U.S. dollar. The Fund typically invests in a basket of Asian currencies that may include, but are not limited to, the currencies of China, Hong Kong, Japan, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. The Merk Absolute Return Currency Fund (MABFX) seeks to generate positive absolute returns by investing in currencies. The Fund is a pure-play on currencies, aiming to profit regardless of the direction of the U.S. dollar or traditional asset classes. The Merk Currency Enhanced U.S. Equity Fund (MUSFX) seeks to generate total returns that exceed that of the S&P 500 Index. By employing a currency overlay, the Merk Currency Enhanced U.S. Equity Fund actively manages U.S. dollar and other currency risk while concurrently providing investment exposure to the S&P 500. The Funds may be appropriate for you if you are pursuing a long-term goal with a currency component to your portfolio; are willing to tolerate the risks associated with investments in foreign currencies; or are looking for a way to potentially mitigate downside risk in or profit from a secular bear market. For more information on the Funds and to download a prospectus, please visit www.merkfunds.com. Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks and charges and expenses of the Merk Funds carefully before investing. This and other information is in the prospectus, a copy of which may be obtained by visiting the Funds' website at www.merkfunds.com or calling 866-MERK FUND. Please read the prospectus carefully before you invest. Since the Funds primarily invest in foreign currencies, changes in currency exchange rates affect the value of what the Funds own and the price of the Funds' shares. Investing in foreign instruments bears a greater risk than investing in domestic instruments for reasons such as volatility of currency exchange rates and, in some cases, limited geographic focus, political and economic instability, emerging market risk, and relatively illiquid markets. The Funds are subject to interest rate risk, which is the risk that debt securities in the Funds' portfolio will decline in value because of increases in market interest rates. The Funds may also invest in derivative securities, such as for- ward contracts, which can be volatile and involve various types and degrees of risk. If the U.S. dollar fluctuates in value against currencies the Funds are exposed to, your investment may also fluctuate in value. The Merk Currency Enhanced U.S. Equity Fund may invest in exchange traded funds ("ETFs"). Like stocks, ETFs are subject to fluctuations in market value, may trade at prices above or below net asset value and are subject to direct, as well as indirect fees and expenses. As a non-diversified fund, the Merk Hard Currency Fund will be subject to more investment risk and potential for volatility than a diversified fund because its portfolio may, at times, focus on a limited number of issuers. For a more complete discussion of these and other Fund risks please refer to the Funds' prospectuses. This report was prepared by Merk Investments LLC, and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward-looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute investment advice. Foreside Fund Services, LLC, distributor.

Thank you for your interest in the Merk perspective. To serve our audience better and to continue offering our insights free of charge, please enter your information below to continue reading.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||